Three lines of connection run between: the histories of 1930s blues recording techniques, letterpress smoke-proof tests and Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville (printer, typographer and amateur inventor). Smoke Proof sees lampblack soot as the harmonising material which draws these disparate histories together, and enabled recorded sound with a direct link to language.

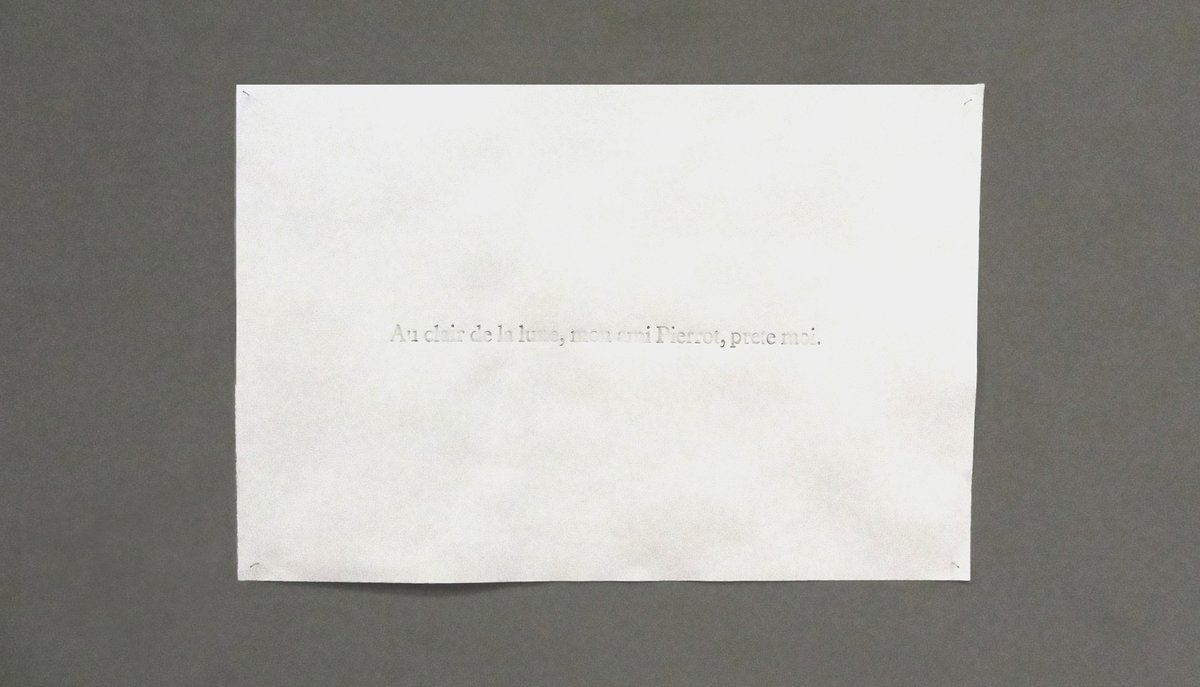

In 1857, de Martinville’s obsession with linguistics led him to make the earliest known sound recording. French folk song “Au clair de la lune” was recorded on his mechanical invention which carved soundwaves into a layer of lampblack soot. The recording could not be played back until it was rediscovered in 2008.

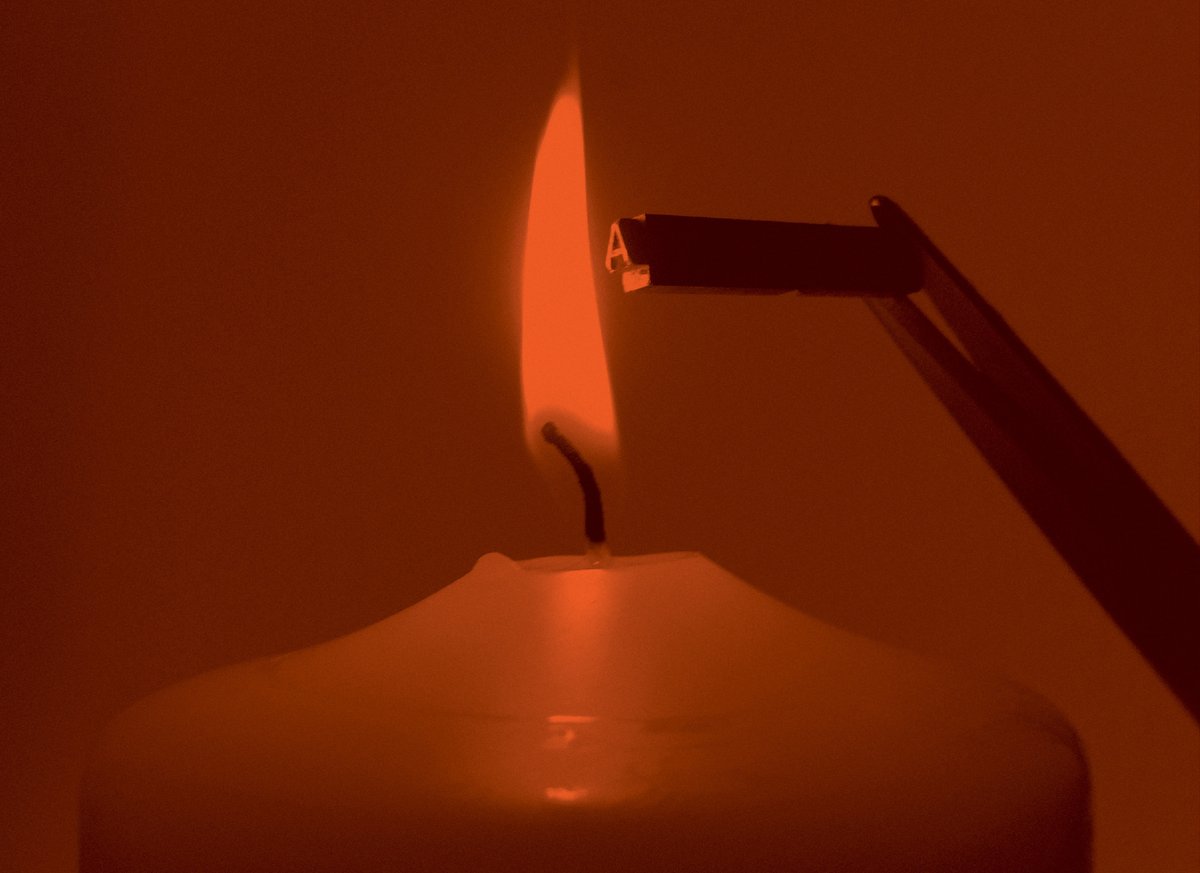

In Smoke Proof, McCartney explores the notion that de Martinville recorded sound by adapting and inverting the temporary printing technique used by typographers to make smoke-proof tests with candle smoke as a quick printing method to test new lead letterforms. De Martinville used lampblack as a recording device to transcribe the sound of human speech in a way similar to that achieved by the then new technology of photography for light and image. He created a machine that would do for the ear what the camera did for the eye.

For the exhibition, McCartney creates a sound installation. Each layer of the 4-channel sound installation is based on a separate recording technique. Each layer in the composition is isolated in its own speaker, to create a constellation of sounds that fill the gallery with the multiple voices that together make up a single composition. The sound becomes sculptural as the space is navigated. The piece is constantly deconstructed, and new compositions are created as different layers of sound in the space are encountered which fade in and out of earshot.